If you click on a link and make a purchase we may receive a small commission. Read our editorial policy.

Dave Chisolm's Enter the Blue dives into the world of jazz, performance, creation, and obsession.

An interview with Dave Chisolm on his newest graphic novel Enter the Blue

Not only is Dave Chisolm a comics writer and artist, he also plays the trumpet, composes, and teaches music. Chisolm's 2020 graphic novel Chasin' the Bird: Charlie Parker in California brought him to a lot of people's attention, and his most recent fiction graphic novel, also set in the world of jazz, Enter the Blue, has made quite a bit of buzz as well.

In this interview with Popverse, Chisolm talks about his research process, the powers of practice, and handling one of comic's trickiest problems: depicting music on the page.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Popverse: So you're a musician, a trumpet player, and a cartoonist. Where and how do comics and music intersect for you?

Dave Chisolm: My whole life is like ping pong, back and forth between my obsession with music and my obsession with comics since before I can remember. So they've always been really intertwined in my head.

When I think about the intersection of the two on a more abstract, formalist level, both music and comics can be heavily rhythmic, both music and comics can experiment with color and changes of style and real form. I think the stuff that that makes me geek out the most in both mediums are examples of each medium in which form and content are married together or working to serve each other.

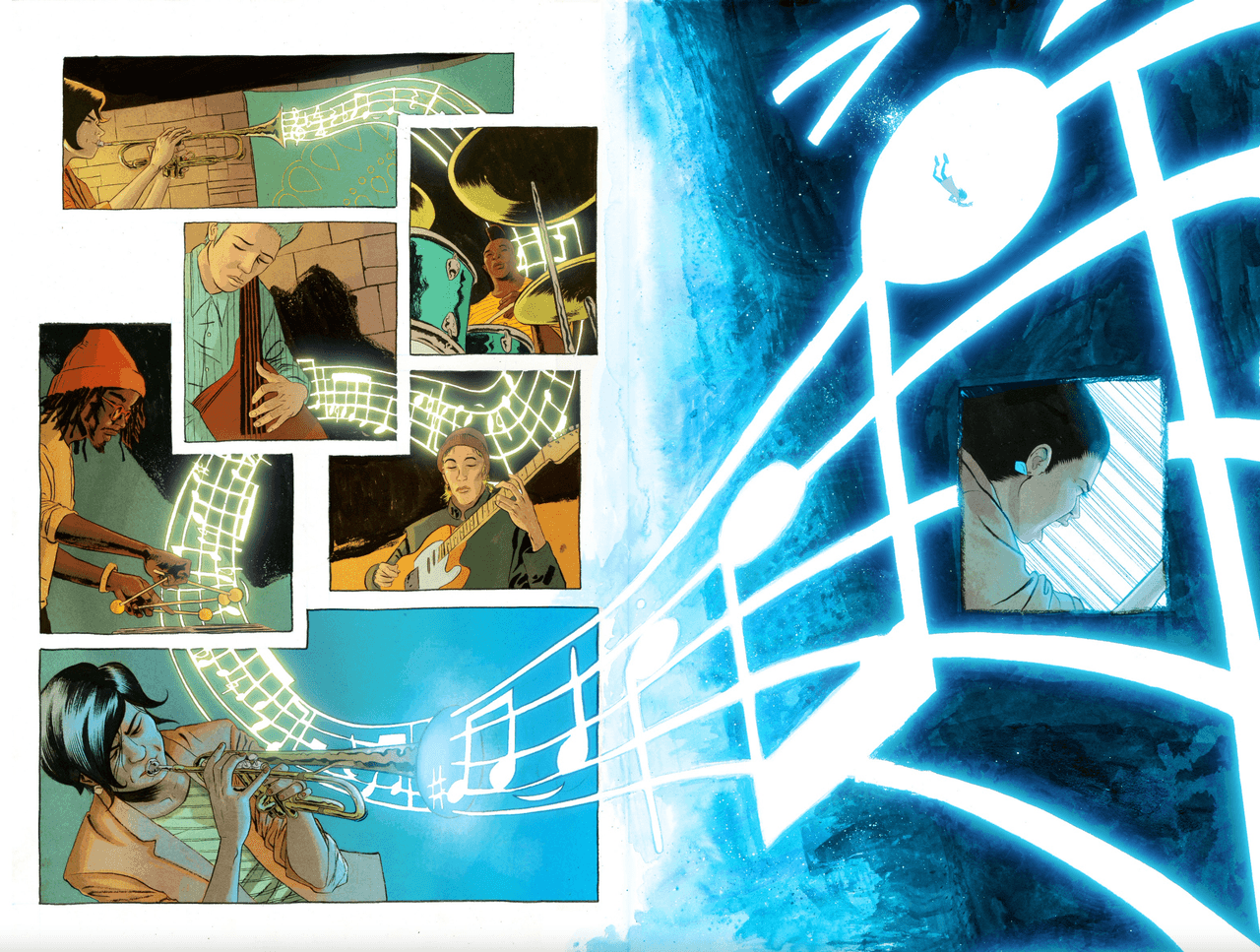

Speaking of form and content, visual representation of music is one of those famously finicky things in comics, but I think your books are a particularly strong example of how it can work. In Enter the Blue, you have some pretty complex music-related layouts. Can you talk about how you lay out these more complicated pages, especially in terms of the music?

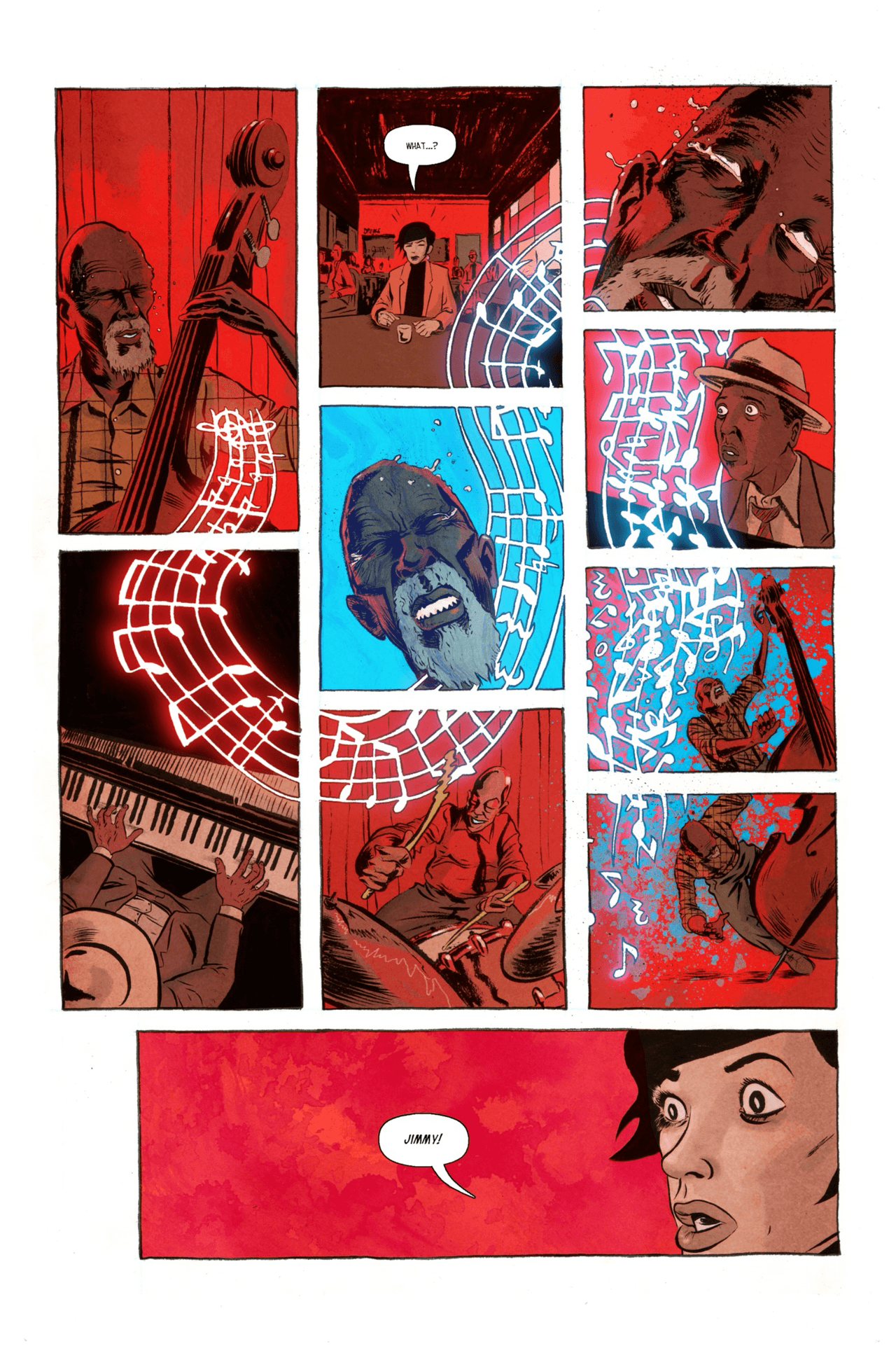

I think one page that stands out in the book is the page where Jimmy collapses. In that page, the panel layout is really confusing until you look at the way that music is flowing through the panels, and then it tells you what order to read the panels in. For typical Western comics, we read left to right first and then top to bottom second, and in this one, the panels, the musical notes immediately go down and then go back up and then go down.

The music notation that I use throughout is really specific. It's put in there with a lot of purpose. It's used to communicate something, oftentimes some extra musical aspect. So in that particular example, you can see that the music notation disintegrates by the end of the passage as the Jimmy character collapses at the gig. All of the previously pretty organized music notation becomes very disorganized and chaotic, as he collapses and drops his base.

For some of the other pages, it was really all built around the conceit of the book and working to serve the conceit of the storyline, which is this idea of the Blue, this fantastical liminal space that you can reach by playing and improvising inside of jazz music. It's usually in the book intended to show the stuff that Jessie [the main character] plays. And then [it's] all about leading our eyes specifically to that one big note that she plays that allows her to transport herself into this magical space.

You mentioned the traditional Western style of panel reading. When you're coming up with your layouts and how you want the page layouts to be, are you drawing from people that you've read or concepts that you're in conversation with? Or are you just sitting down with a pencil and figuring it out?

I wish I could say that I just have no influences at all; I was born out of the forehead of Zeus like perfection! But no, I am just like everybody else. I pull a lot of inspiration from a really wide variety of sources— from Calvin and Hobbes Sunday strips, especially after Bill Watterson kind of pressured the syndicates into letting him use his Sunday space more freely, and not quite so gridded out. And then ranging from that to something kind of lowbrow, like Todd MacFarlane's Spider-Man stuff from the 1990s was really important to me and some of the earliest comics that I made back then. And the work of [Katsuhiro] Otomo on Akira is always a touchstone for me, in particular the later chapters, where you really get into this weird psychedelic kind of dream space.

JH Williams III is a huge influence for me, like his work on Promethea and the few issues of Batman that he did, and then the runoff Batwoman that he did. He's just great. But what really makes me excited about that, there's two things really. One is using unusual layouts or formal devices specifically because of how they offset to what's typical. So making sure that in a book like this, that there's a real sense of typical with the present day story of Jessie and the real world, to set up ground rules for that section so that, when they go into the Blue, the rules can be thrown out. The contrast between those two things is a really powerful story telling tool.

In particular, when those storytelling elements can follow the form and function, this can be meaningful in [a] symbolic way to what's happening internally for the characters.

You mentioned earlier that comics and music have been with you your entire life. There's a lot in your book about the creative aspect of art and the ongoing conversation with other artists, as well as performance. It seems like a very personal work. Can you talk about how the story came about?

I think the inception of it all is pretty funny actually, because I was just wrapping up the Charlie Parker book that I did for Z2, and they approached me about doing a book pitch for Blue Note Records, and so I pitched a nonfiction book to them. And in the Zoom meeting I could tell they hated it. I was like, 'You guys hated that pitch, didn't you?' And they were like, 'Well, we were hoping you'd pitch a work of fiction.'

And then it really sort of snowballed in my mind in that meeting. I was like, 'Well, we want it to be about the history of jazz, but also about the future of jazz, so we want a teacher and a student— it has to have a mentor and a mentee character, because that's so crucial to the lineage of this music. Then there needs to be an underlying sort of hook or mystery that pulls the story forward. So maybe the teacher goes missing.' And then I said, 'Why don't you give me two weeks, and I'll figure it out.'

I got off that call, and thankfully my wife Elise is an incredible story doctor. She's great at noticing when a moment is not emotionally earned and all of these things that are easy to miss. And she's also a musician; she's a cellist. I started talking to her about that because in all my years of music, I didn't have, a lot of really, really great relationships with teachers. It's probably my fault, not to blame my teachers. I think that I'm a bad student in the sense of I'm best at teaching myself, and I think I just have problems with authority figures.

So I've always been someone who just follows my own path to knowledge and skill. And so I started talking to her, like, 'Well, what's this character? How does this work?' And it all really stems from those conversations with her.

I had a few other conversations with a couple friends of mine who acted as sensitivity readers for the book, a trumpet player based in New York City who lived in Rochester for a while named Brandon Choi, who's like really an amazing player. And then also a guitar player who's based in Nashville named Cynthia Kelly, talking to them a little bit just to make sure that there was some authenticity there and everything.

Ultimately, I think the relationship between Jessie and her teacher Jimmy is inspired mostly by my wife's relationship with her teachers that she had at Eastman [School of Music]. When she was getting her bachelor's and master's degree in cello performance, and they still live in Rochester as well. And we see them fairly often even though she hasn't been their student for like a decade or something like that now.

Jessie struggles with performance, and I think that's something that most people who deal with performing music, have encountered in some small or large way in through their upbringing and music and everything.

So, it seemed like it just made sense to put all that stuff together. The other thing is that I knew that Jessie was going to be a music teacher, but I didn't want to present teaching music as less than performing music like so often happens in like media— to say this is actually really worthy, what she's doing, but it doesn't mean that her relationship with performing needs to be gone. They're not mutually exclusive in any way.

Speaking of how media depicts art, a lot of art about creating art glorifies obsession, but Enter the Blue tries to break with that concept. What are the dangers of obsession to an artist?

Well, first off, I will say that I think that you can't get really great at something without having at least a stretch of time in your life where you're consumed by the thing, right? So obsession, I'm not gonna like throw it out completely. I think that it's really valuable.

I mean, it depends on the person. But then, you know, I think for a character like Jessie, I think that she's someone who did obsess about this music and then kind fell flat because the more she obsessed, the more she realized she didn't know. It kind of pulled the joy out of it for her, for that time being. And then she had that comparison trap with her peers, and so her obsession kind of opened up the whole ocean. If she was like in a pond, then her obsession became this like big massive scary thing.

I'm not sure that I have a satisfying answer to that question, actually, because I think the other part in the book that really talks about this is with Sherm, like, 'You're just obsessing. You're in a dangerous spot.' And you can read that as a pretty easy allusion to the addictive side of obsession, the kind of compulsive side to it.

That's also a pretty well-worn path in jazz media, right? With Charlie Parker and all of these figures in jazz history who have substance abuse problems and stuff like that. So I don't know, it just felt like a message that Sherm would say in that moment. So yeah, it's tough. I don't think I have a good answer for that question.

In Enter the Blue, you depict historical jazz figures in this fictional context, interacting with Jessie in the Blue. What was your research process?

I knew I had to have a few figures from jazz history show up, and I knew that I also wanted it to represent the diversity of jazz music. There had to be at least one person who wasn't part of that subset of people. So I kind of had to search for that, and then I was like, 'Well, Jessie, the main character is a woman, and there has to be a figure from jazz who's not a dude, even though, just like every other bit of music history, it's dominated, it's all written by men about men, even though there are plenty of women.'

I think I had five slots, there's Art Blakey, Duke Ellington, Charlie Haden, Louis Armstrong, and Billie Holiday. I knew there had to be someone who was really strongly associated with Blue Note Records, so Art Blakey became that person. So then I just went and looked up every Art Blakey interview that I could find, in print and film, and I transcribed everything I could that was potentially useful for in this book. And I did the same for Duke Ellington.

Charlie Hayden seemed like a good bet because I wanted someone to represent free jazz as well, for pushing boundaries. And then, I looked at bunch of quotes from him. And thankfully, there were like a plethora of great historic quotes from him. I knew Louis Armstrong had to be in it because he's one of the first significant really early figures in jazz music, and then for Billie Holiday it all just kind of fell into place. Writing all those, I would say like between 60 or 80 percent of what all those characters say are adaptations of historic quotes from interviews by them just kind of woven into the conversation with Jessie.

Earlier, you mentioned Jessie's issues with performing. There's a lot of specificity there in the book. Can you tell me about your experiences with this kind of creative doubt?

I think in a lot of ways I have the opposite problem. Which is kind of embarrassing to say, I suppose. I think it's maybe kind of annoying to say. But I think that the imposter syndrome that I get is that if people don't like my art, that they're an imposter— and sometimes that is terrible. I think that has led to points in my life of very slow growth as an artist or creator.

It makes me think of this interview with this jazz composer named Bob Brookmeyer where the interviewer asked him, 'Who's your favorite composer ever?' And he said, "Bob Brookmeyer." And the interviewer was like, 'Oh, are you worried that you sound conceited and arrogant?' He's like 'Well, who else can I trust to write what I want to hear?' I think there's a real lesson in that. But at the same time again I think having some humility...

I don't look at my old work and feel absolute shame like a lot of artists do, and I don't finish my day looking at the work I've made and feel horrible about it. I usually am like, 'Oh this is really fun and cool' and 'I can't believe I get to do this.'

There have been times where-- I had a two year long gig where every week I would play solo guitar and singing. Trumpet's my main instrument, and I think that was probably the closest I had to having imposter syndrome. But looking back, I think it was still kind of like playing at a crowded bar. Like nobody gives a shit about the sad guy playing guitar in the corner, and so I don't know. But I've seen it a lot in other people and I've definitely felt nerves playing in front of people.

I always tell my students the best trumpet you'll ever play in your life is at a wedding gig where nobody gives a shit, and as soon as you have to play trumpet in front of anybody who you admire, nothing works. You have your worst day and your best day, and practicing isn't about [your best] day it's about [your worst] day. We want to bring [your worst] day up. If we can bring the worst day up, your best day gets better, but you want to make it so that when nothing is working and you're having your worst day, nobody knows except for you. That's the goal of practicing, and I suppose it's probably the same for art .

Enter the Blue is currently available for purchase at comic shops, bookstores, and online. Follow Dave Chisolm on Twitter and Instagram.

Making the invisible visible: An interview with Jesse Lonergan, creator of Hedra .

Follow Popverse for upcoming event coverage and news

Find out how we conduct our review by reading our review policy

Let Popverse be your tour guide through the wilderness of pop culture

Sign in and let us help you find your new favorite thing.

Comments

Want to join the discussion? Please activate your account first.

Visit Reedpop ID if you need to resend the confirmation email.