If you click on a link and make a purchase we may receive a small commission. Read our editorial policy.

Why The Conjuring is Hollywood's most conservative horror movie franchise

The Conjuring movies & the peculiar fictional afterlife of the real Ed and Lorraine Warren.

Popverse's top stories

- "And my axe!" Lord of the Rings star John Rhys Davies says there's one world leader who deserves Gimli's iconic weapon

- Wonder Man is the Andor of Marvel Studios’ modern TV series on Disney+

- Absolute Batman happened because DC Comics writer Scott Snyder got bored reading about ‘superhero fatigue’

This post includes spoilers for The Conjuring: Last Rites.

The Conjuring: Last Rites is both a loving farewell to Ed and Lorraine Warren, and a passing of the torch to their daughter Judy (Mia Tomlinson) and her future husband Tony (Ben Hardy). With the Warrens now semi-retired from their career as paranormal investigators, the film drops hints that Judy will follow in her mother’s clairvoyant footsteps, acting as a coming-of-age story for her possible future as a ghost hunter.

After years of trying to block out her disturbing supernatural visions, Judy eventually decides to use her powers for good, joining her fiancé and parents in exorcising a haunted house. Then, in the epilogue, both couples get a happy ending. Judy and Tony have a big church wedding with cameos from characters the Warrens saved in earlier movies, and Ed gives Tony the keys to their museum of cursed objects, signalling that he trusts Tony to take some responsibility for the family business.

Before that happens, however, Tony must graduate through a classic heterosexual ritual, proving himself to the family patriarch.

During a long sequence at Ed’s birthday barbecue, a familiar parental dynamic plays out: While Lorraine thinks that Tony and Judy make a cute couple, Ed is reluctant to accept a new man in his daughter’s life. So when Tony asks permission to marry her, Ed argues that six months is far too soon to propose - even though he and Lorraine got married after a similarly brief courtship.

Even after a bit of male bonding, with the women watching fondly as Ed and Tony play table tennis in the garage, Ed still sees Tony as a disruptive presence in his baby’s life. Fortunately, Tony does manage to prove his masculine credentials in the end, first by helping to fix Ed’s motorbike, and later by risking his life during the film’s explosive supernatural finale.

These family dynamics are just one way in which this movie - and the Conjuring franchise in general - feels unmistakably conservative.

Both creatively and politically, these films tend to avoid taking risks. In fact, 50 years on from The Exorcist, they actually feel less subversive in their exploration of supernatural horror, carefully shying away from moral ambiguity. They’re straightforward tales of Catholic good defeating demonic evil; a formula that’s brought the franchise enormous commercial success, reusing familiar Christian horror tropes while sanding down any rough edges. For instance, Last Rites adapts the story of the Smurl haunting, a Pennsylvania family who reported years of paranormal incidents in their home. But instead of covering the most disturbing detail of the Smurl story - the parents’ lurid account of being sexually assaulted by a demon - the film opts for a more blockbuster-friendly scenario involving a cartoonish axe-wielding ghost, a cursed mirror, and a corny cameo from the franchise’s iconic Annabelle doll.

The Conjuring: Last Rites purposefully downplays the most interesting themes of horror stories about haunted houses and demonic possession - i.e., the sense of powerlessness in the face of violation by a supernatural force. Yes, the Smurls experience some threatening moments and jump scares, but the film generally steers clear of psychological horror. Its main priority is giving the Warren family one last big mission, wrapping up with a happy domestic ending.

The Conjuring movies & the peculiar fictional afterlife of the real Ed and Lorraine Warren

Repeatedly reminding us that they’re based on true events, the Conjuring movies have turned the real Ed and Lorraine Warren into blockbuster heroes, giving them a peculiar afterlife in popular culture.

In reality, the Warrens did indeed build a successful career as ghost hunters, with Lorraine claiming to have clairvoyant abilities, while Ed styled himself as an expert in demonology. Along with investigating cases like the Amityville haunting and the Annabelle doll, they gave lectures on occult phenomena, appeared on the talk show circuit, and published bestselling books. They had a unique impact on our image of paranormal investigation, preceding The Conjuring with numerous earlier horror movies, documentaries, and news reports. Meanwhile, skeptics have debunked many of their cases, including strong evidence that Amityville was a hoax. If you don’t believe in the supernatural, it’s easy to dismiss the Warrens as either credulously naive or outright fraudsters; a pair of relentless self-publicists who spent decades creating pseudoscientific evidence for ghost stories.

Speaking as someone who loves horror but doesn’t believe in ghosts, I don’t necessarily care if studios promote this kind of movie as “based on true events.” However, I do think it’s worth noting how the Conjuring films choose to fictionalize their source material, branding the Warrens as charismatic heroes whose lives are defined by a solemn moral duty.

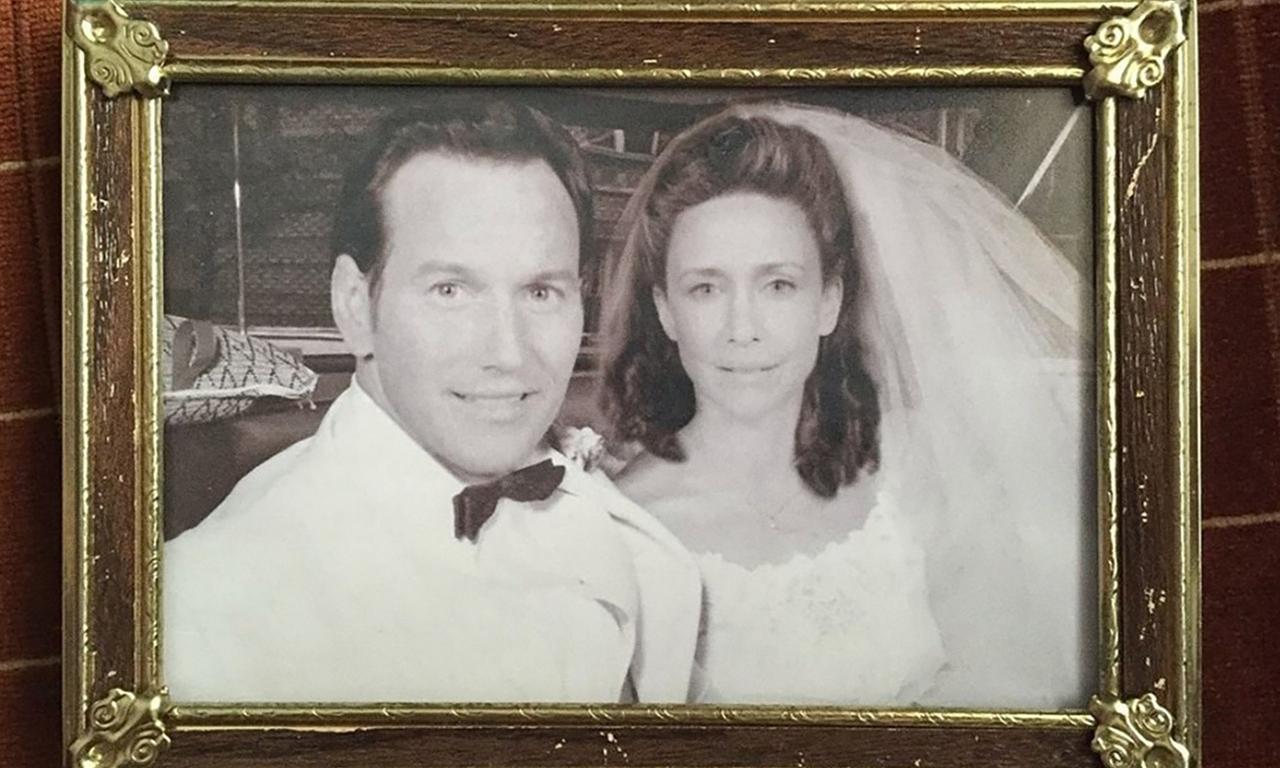

Throughout the four main Conjuring movies, the Warrens’ happy marriage is a bulwark against the forces of evil, presenting Ed as a hunky protector for the sensitive Lorraine. They’re the perfect team, swooping in to protect vulnerable families from supernatural attacks.

Borrowing the outline of real cases like the Smurls’, the Conjuring movies ramp up the tension with CGI monsters and perilous final acts, as the Warrens risk body and soul to exorcise their latest enemy. Their methods are, of course, staunchly Christian, echoing a long tradition of American Christian horror cinema, and tapping into the popular belief that Bibles and crucifixes act as a kind of ghost-repellent.

Vera Farmiga and Patrick Wilson are undeniably charming in these roles, but there’s a weird undercurrent to their dynamic once you learn about the franchise’s creative origins. When Lorraine Warren first signed on as a consultant, she made a curiously specific legal agreement with the studio, shaping how she and her husband would be depicted onscreen.

According to The Hollywood Reporter, "The films couldn’t show her or her husband engaging in crimes, including sex with minors, child pornography, prostitution, or sexual assault. Neither the husband nor wife could be depicted as participating in an extramarital sexual relationship." This news came out following accusations that Ed had a decades-long affair with a woman who was underage at the start of their relationship, and who (according to the woman in question) was allegedly pressured by Lorraine into having an abortion.

We’re all used to seeing biopics and historical dramas that play fast and loose with the truth, often to make their protagonists more likable. Yet there’s something insidious about how the Conjuring franchise has thrived on creating this absurdly wholesome image of the Warrens. The Conjuring: Last Rites lives and dies on our investment in their marriage, spending as much time on their family life as it does on the Smurl haunting. Once they’ve disposed of the ghosts, the film lingers on a schmaltzy epilogue where Lorraine describes a vision of their blissful retirement while dancing at Judy and Tony’s wedding.

In order to set up the generational handover between Judy and her parents, the film also fabricates a relationship that didn’t exist in reality. Although Last Rites depicts the Warrens as a close-knit family unit, the real Judy was mostly raised by her grandmother. Ed and Lorraine were too busy touring the country to raise a child, and when Judy did briefly live in their house, she says she found it frightening thanks to her parents’ tales of the supernatural. The film is correct in saying that Judy eventually embraced some elements of the family business, but that didn’t happen until later, when she took over their museum of occult artefacts.

This tension between fact and fiction plays a curious role in the films’ political subtext. Among Hollywood's biggest commercial horror franchises, The Conjuring offers a notably conservative atmosphere, from the films’ focus on domestic sentimentality and simple moral themes to their uncritical take on Christian exorcism tropes. Filmed with a cosy undercurrent of late-20th-century nostalgia, they quietly adhere to old-fashioned gender roles and family values. And as is often the case for examples of conservative nostalgia, they reflect a rose-tinted, carefully curated version of reality.

Here's how to watch all Conjuring movies (and spin-offs!) in order.

Follow Popverse for upcoming event coverage and news

Find out how we conduct our review by reading our review policy

Let Popverse be your tour guide through the wilderness of pop culture

Sign in and let us help you find your new favorite thing.

Comments

Want to join the discussion? Please activate your account first.

Visit Reedpop ID if you need to resend the confirmation email.